On Monday March 3, at 2:05pm Pacific Time, a satellite built by small Sydney start-up Space Machines Company (SMC) hitched a ride out of Earth’s atmosphere on one of SpaceX’s 70 metre long, 550,000kg Falcon 9 rockets.

The Australian trade and Investment Commission heralded the launching of SMC’s vessel, dubbed ‘Optimus’, as a “trailblazing satellite to clean up space junk”.

SMC lost contact with Optimus a month after launch, consigning her, with tragic irony, to the status of space junk.

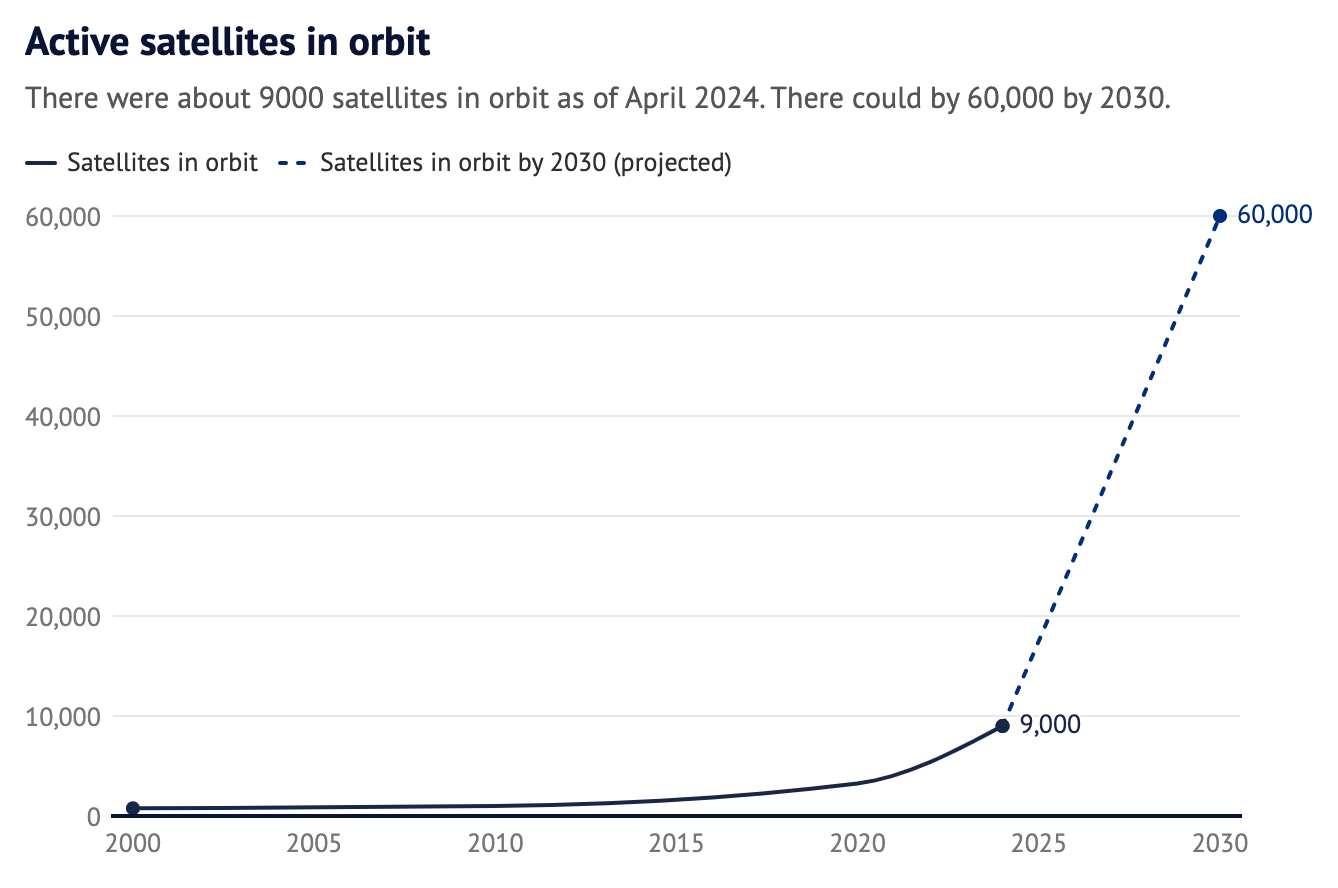

According to the European Space Agency, Optimus is one of 35,000 large objects, including 26,000 pieces of debris and 9000 active satellites, pelting laps around Earth. Added to the traffic is another million pieces of debris under 10 centimetres in diameter.

By 2030, there will be 60,000 satellites in Earth’s orbit, more than six times as many as there were as of January 1 2024.

Despite persistent and pervasive encouragement to chase growth, perfection, status and control, we all need reminding of our smallness.

There is no experience better equipped to deliver this reminder than a minute spent staring into the night sky.

For hundreds of thousands of years man has shrunk himself into narratives of unfathomable scale, painting lines that straddle the lightyears of space between stars and planets to create pictures of the familiar. Bulls, scorpions, eagles, chariots, and gods.

And for hundreds of thousands of years, too, man has used these narratives as scaffolding in our everlasting and insatiable desire to understand ourselves and our place in the universe.

From ancient cave paintings to the birth of Christ, and from man’s first forays into space exploration to zodiac-informed life advice, we use the stars to paint ourselves into a greater story. We are a species whose every development—be it spiritual, artistic, or scientific—has been spurred in response to our relationship with the cosmos.

While I may suffer from a very human inclination to vie for control and relevance and certainty, it only takes a moment pondering my cosmic significance—or lack thereof—to be reminded that these inclinations are, in the grand scheme of things, aberrations.

Beneath a star-lit sky there is scant space for hubris. The ant cannot un-see how small he is after meeting the shadow cast by the sole of a moving boot, how pathetic his plans and how meagre his ideas after reckoning with scale and time and the inconceivably larger other.

Beneath the stars, and dwarfed by the immensity of the great unknown that they demarcate, we are humbled into our very humanity.

I am an ant. No, I am a bacterium on an ant’s mandible. Primordial ooze, purposelessly evolving limbs and teeth, or just a flickering moment in some inconceivable being’s dream, soon to be forgotten.

At the end of every day we are all reminded, should we look up, of our smallness.

It is 2024 and the air between Newtown and the stratosphere is quickly being turned into a monument to humanity’s malnourished soul. I walk up King street, doing my best to prevent Lacey from licking the pavement clean, which on a Friday night becomes a buffet of kebab drippings and melted ice cream. When we get to Camperdown park I let her off the lead, walking a few laps before sitting on a rainbow coloured bench while Lacey sniffs around in the grass.

The light and air pollution have me glancing up at one of not-many stars visible to the naked eye, only to notice that it’s moving in a slow, mechanical line across the sky. The blue and red lights of a cop car flash along the edge of the park, and the distant pop of fireworks spooks Lacey back from the grass and to my side.

Ten-odd metres to my left, a woman on a picnic rug balances a fair-haired toddler in denim overalls on her knee. She scrolls on an smartphone with her left hand, her right arm fastening the toddler to her lap. The toddler stares into an iPad, which plays a cartoon I don’t recognise, and I watch the satellite disappear behind haze.

This morning I read that Elon Musk has been tasked with the role of leading Trump’s new Department of Government Efficiency (Doge). I wonder how many more satellites—soon-to-be-space-junk—we’ll have to hurl into the sky before the only visible celestial bodies left are mere testaments to our own short-sightedness.

I consider Optimus, the “trailblazing satellite”, who has become an example of the very space junk it was intended to “clean up” while my dog waddles up and down the median strip out the front of our house having King Street Buffet inspired diarrhoea.

We speak at length of the age we now know as the Anthropocene, often with reference to our species’ physical effect on the planet. But what of the Anthropocene’s effect on us? On who we are, how we think, and how we relate to the universe beyond? How might we be altering the environment in ways that ultimately alter us?

What kind of a mind is produced in a post-Anthropocentric world? A world where a human must trawl through photographs and history and poetic musings for a whiff of humility or awe?

What kind of human is born of a planet surrounded not by the unfathomable and unknowable, but by conquest?

I worry for generations to come. Generations whose access to skyward wonderment and cosmic perspective may dwindle in congruence with man’s techno-hubris. We talk a lot about the physical degradation of the planet, lamenting how our careless pollution of the land, water, and atmosphere will affect our children.

But what of the space between ourselves and the rest of the universe? This space, if nothing more, is a shared lens facilitating man’s relationship with himself and the wider world since he first looked up.

What might replace the perspective-inspiring effect of cosmic wonder come the day that our night skies are replaced by smog, satellites, and space junk? Can this shared lens be decluttered and repaired, or are we slowly committing ourselves to an existence severed off from the pre-Anthropocene?

I liked this one mate, it’s a good reminder of how small we really are x