Australia does not censor radicalised artists. [pub. in The Australian 25/2/2025]

Published in 800 words by The Australian 25/2/2025

There is no line separating artists’ work from their politics. Despite what Memo Review might have you believe, this is not the fault of Australian government body Creative Australia. This is the result of artist-on-artist censorship.

If there were ever a day and age in which artists on the whole might have represented countercultural thought or boundary-pushing ideas, it is not this one.

The most poignant example of this in living memory occurred last weekend in the form of a letter penned by Memo Review, signed by thousands of artists and shared by thousands more.

The letter lambasts Creative Australia’s withdrawal of 2026 Venice Biennale representative Khaled Sabsabi, rendering the decision an affront to Australia’s cultural sector amounting to ‘artistic censorship’. While at face value the letter appears to champion artists’ rights, it raises far more questions than it addresses.

Censorship in the Arts

Australia’s arts sector is a notoriously dangerous space for free speech, artists constantly limiting each others’ freedom of association and expression with bullying and public shaming. From the mass-doxxing of 600 Jewish artists by their fellows to bi-weekly cancelations on ever-brittle grounds, so-called ‘creatives’ have done their very best to censor themselves for quite some time.

And so while censorship is a word usually reserved for state interference, as addressed by the Memo Review, artistic censorship in Australia is overwhelmingly the result of artists keeping unhealthy and vindictive tabs on other artists.

Any artist who has ever had to field questions like, ‘why didn’t you sign our petition?’ understands the stakes at play.

Popular slogans like ‘silence is violence’ keep artists who so desperately would much rather focus on their practise and maintain their integrity in a state of perpetual anxiety.

That a sector so incapable of tolerating free thought would maul the hand that feeds over perceived censorship beggars belief. The notion that an artist ought to feel ashamed, belittled, or fearful for simply wanting to be an artist and not a spokesperson for others’ agendas is a tragedy. For every artist in this position, I am so, so sorry.

Unlike almost every Jewish artist in the country, there are no limitations on Khaled Sabsabi’s ability to freely express himself or freely associate. In comparing Sabsabi’s current predicament with artists whose practices and reputations have been warped by real censorship, it feels wrong to put both in the same camp. Any real open letter designed to address censorship would have been penned and disseminated long before Creative Australia’s recent stuff up.

Where to draw the line?

Memo’s open letter focuses on Creative Australia’s ineligibility to make concrete claims on the interpretation of Sabsabi’s earlier works – namely, one that may appear to deify Hezbollah’s Nasrallah, and another that may appear to give thanks for the September 11 attacks.

Many now wait for Sabsabi to address Creative Australia’s alleged misinterpretation of his work with a statement explaining his feelings towards mass murderers. One might argue that he shouldn’t have to — but for $100,000, a trip to Italy, the opportunity to sue Creative Australia for damages, and the opportunity to vindicate the arts sector for standing by him, there is only one reason I can think of for why Sabsabi might not feel comfortable clearing things up.

Memo Review and their supporters make the very reasonable claim that “[Creative Australia’s] decision effectively acts as an interpretation of the political acceptability of the selected artist’s work.” This is a notion that I agree with in principle. But having seen some of the artists who Creative Australia have awarded grants to, I’m concerned by the possibility that there may be no scope for this government body — according to Memo — to draw a line in the sand somewhere between funding artists and greenlighting projects hatched by people like Matt Chun.

Chun was awarded $42,000 by Creative Australia, a decision that was met with no open letters by Memo Review nor any public outcry among artists. If this doesn’t make you sick, I’d love to know what would.

The argument that a government body should feel forced to hand over large amounts of money and praise while both being ineligible to interpret an artist’s work and intentions, nor allowed to assign funds based on that interpretation, misunderstands the role of government. It also suggests that while there may be no correct way to interpret an artist’s work, that there is an incorrect way.

While I understand the real fears of a government restricting creative expression, we simply don’t live in a country where this is a problem. I also don’t buy the slippery-slope argument that to-ing and fro-ing over Sabsabi’s contribution to the arts denotes a government crackdown on freedom of expression. The fear-mongering that this episode may lead to instability in future arts funding is a red herring invented by those who have no objections to the current state of affairs. I repeat, Matt Chun received $42,000 from Creative Australia.

The terrifying reality of Australia’s art world is that radicalisation is not just in vogue, but is entitled. The radicalised now feel entitled to spout hate speech and vilification, so many having received government funding to do exactly that.

Watching artists mistake extremism for counterculture, bigotry for boundary-pushing, and edginess for creativity has been soul-crushing.

While government oversight in creative expression is troubling, choosing who to give and not give inordinate sums of cash to does not amount to ‘censorship’.

Here is one of many, many examples of the problem:

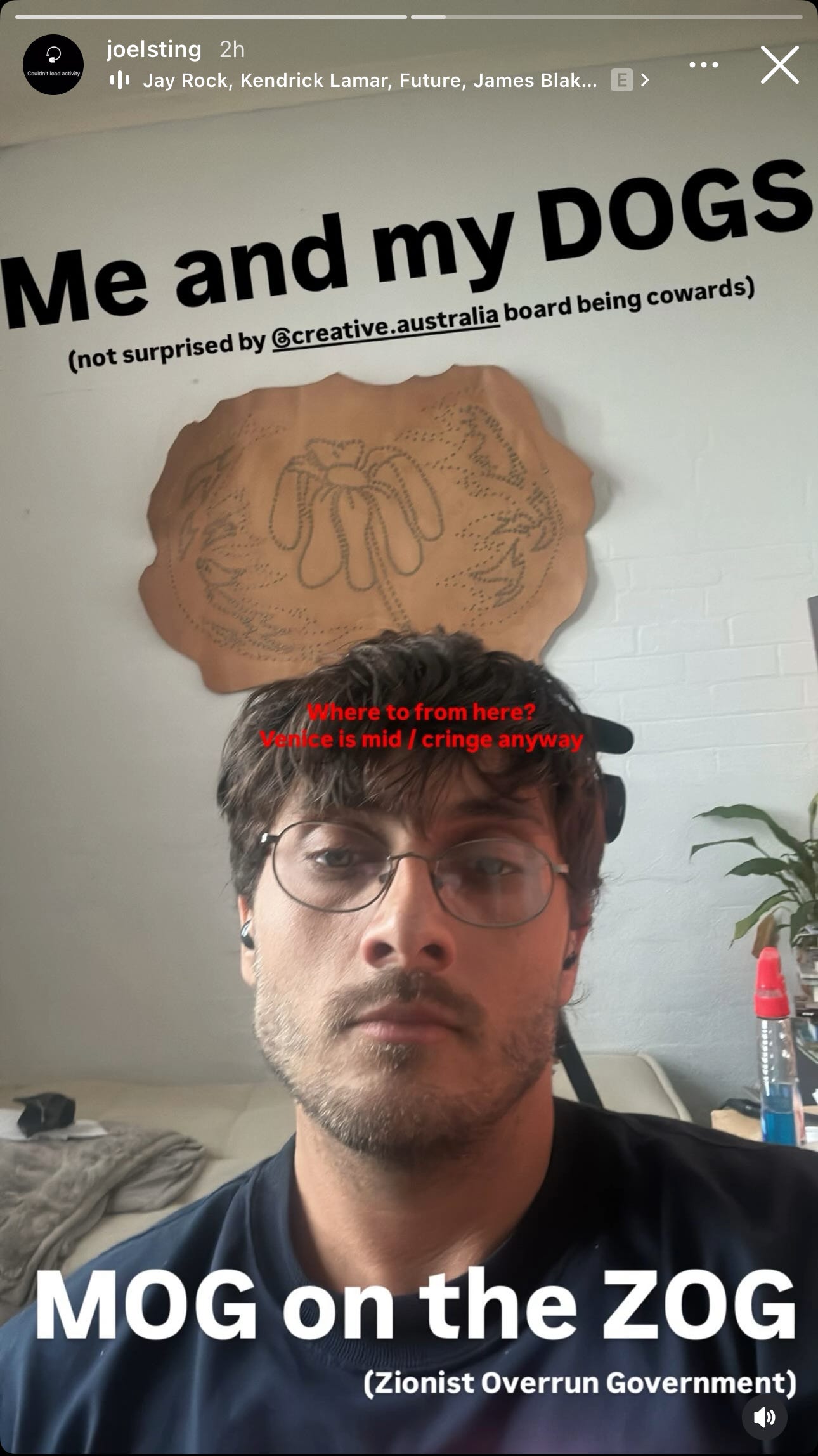

Joel Spring is a member of Australia’s emerging art world royalty, as well as being the beloved son of one of Australia’s most prestigious commercial gallerists. Spring has received tens of thousands of dollars in Creative Australia grants and government accolade. Spring is also shortlisted with 5 others for a $30,000 government grant known as the ‘Create NSW and Artspace 2025 NSW Visual Arts Fellowship (Emerging), while publicly posting videos of Jewish children being bullied.

These videos sit wedged in-between work praising Sinwar, Hamas and Hezbollah for all at Creative Australia to see, Spring — like so many other Australians — having experienced a form of psychological transference onto the Levant’s Arab population.

Despite being under consideration by Create NSW and Artspace for this most prestigious of grants and accolades, Spring uploads content encouraging people to start fires at Artspace events. Strangely enough, Artspace and Create NSW continue to platform him on social media.

While regularly uploading flagrantly racist material — often with a peculiar obsession around racial identity and blood quanta, reminiscent of identity politics’ most vile qualities — Spring posits that he may be immune to accusations of bigotry due to being of Indigenous descent. And of course, in the aftermath of Creative Australia’s rescinding of Sabsabi, Spring blamed the Jews.

Those artists closer to the bottom of the pile suffer considerably less scrutiny than Sabsabi (and Jews for just being Jewish) have. They seem eligible for funding and accolade with scant oversight, and I hope that scrutiny over the Sabsabi affair at Creative Australia compels a closer look at some of the piggies further down the trough.

For example:

• ‘un Projects’ — a subsidiary of ‘un Magazine’ — publishes writing that, according to their website ‘emerges from art making, providing an independent platform for discussions about local artistic practice’.

• West Space, according to their website, ‘is an independent, non-profit contemporary arts organisation.’

‘West Space combines the flexibility and creative freedom of an artist-run initiative, with the professional infrastructure and curatorial support of a larger public institution.’

Both un Projects and West Space continue to fund, bestow accolade, cross-promote, and platform Mr Spring, among a host of others with very similar public profiles. un Projects are a registered charity, listing The City of Yarra, Australia Council for the Arts, City of Melbourne, and Creative Australia as financial supporters on their website.

West Space is supported by Creative Victoria ($100,000 annually from 2022-2025) and Creative Australia ($100,000 annually 2025-2028).

Perhaps a little discernment in Creative Australia, along with other government arts-funding institutions, wouldn’t hurt.

And please do remember that Mr Spring is not just one little example of a person who should not be in any way able to access government money; not just one little anomaly who managed to slip through the cracks at all levels of the art world.

Rather, he is the living embodiment of a very safe and very well funded pocket of Australian culture who have managed to turn peddling hatred into a government rort through a network of like-minded individuals and institutions.

From West Space to the Biennale, and from The City of Yarra to Creative Australia, radicalisation and antisemitism have become as fashionable as tattoos and distressed caps.

While those who deem it appropriate to boycott Jews for being from Israel (independently of those Jews’ personalities or politics) are insisting on the opposite approach when it comes to any other member of the community, we have a serious problem. Because if this double-standard isn’t antisemitic, from Spring to Sabsabi then what is it?

The friend who sent me this screenshot from Spring’s Facebook story, as well as a collection of other screenshots and screen recordings, also sent them to Create NSW immediately after he was awarded his most recent grant. For a small selection taken from a much larger collection of Mr. Spring’s contributions to the discourse, see here.

And while I feel troubled by having drawn attention to Spring, I urge you to not to target him personally. He is more a symptom of a problem than its cause — like one of millions of cancer cells, growing and dividing. Healthy cells, much like average artists, follow a typical cycle: they grow, divide and die.

Cancer cells, on the other hand, don't follow this cycle. Instead of dying, they multiply out of control and continue to reproduce other abnormal cells. They feed off a body unable to determine between cancer cell and healthy cell.

Despite Memo and her signatories’ concerns, it’s the granting of government funds to artists like Joel Spring and Matt Chun that has many believing that a little bit of discernment in the Australian arts grants processes might not hurt. It is this lack of discernment that feeds this cancer, giving cells life far beyond their worth.

Nobody said chemotherapy was pleasant. But without serious treatment, this cancer will kill the arts. This cancer will soon affect all artists’ capacity to access government grants as Federal government(s) will soon use the chaos at Creative Australia as an excuse to ‘restructure’ (de-fund).

While it may feel like silence in the face of rampant antisemitism, or grumpiness about ‘government overreach’ might be the solution to one’s feeling of security in the Australian Arts sector, the truth is that without removing this cancer all Australian artists will soon lose the lifeline afforded to them via Creative Australia.

And so, the survival of the arts is contingent upon dealing with this cancer head-on. The survival of the the arts is contingent upon the taking of a searching and fearless moral inventory among those who believe that it is the state’s responsibility to unquestioningly fund bigotry (and no, I’m not referring to Sabsabi).

As unpleasant as it is, we are left with two options: ignore the cancer, or treat it. I believe in treating it, and I believe that we start cutting out tumours immediately.

This begins with an overhaul of grants selection processes.

I draw your attention to Yoni Bashan and Nick Evans February 14th Margin Call column in the Australian, ‘A creative flip-flop over terrorist imagery and arts grants’:

"An analysis of the grants being doled out by Creative Australia also shows a surprising level of affiliation between the people on the assessment panels and the recipients making their case for funding. Our attention was drawn to those who are amply connected through an artist’s body called Eleven Collective, started by Sabsabi in 2016. Its 14 core members have collectively received about $1m in grants since 2018.

Among them is Hoda Afshar, an artist awarded $71,000 by Creative Australia, including a grant valued at $35,635 and assessed by two artists – Abdullah Syed and Abdul Abdullah – both of whom are linked to Afshar through the Eleven Collective group. Syed and Abdullah also sat on a separate panel that in 2023 awarded $45,200 to another Eleven Collective artist, Shireen Taweel.

We asked Creative Australia about these coincidences. It told us that “robust processes” are deployed to ensure “transparency and independence of decision-making”. Fine, very well. So we then asked them to produce records of any conflicts being declared for the cases mentioned – we received no reply.”

Free speech or free money?

With regards to Sabsabi, we have to remember that not all refusals to bankroll artists nor reconsiderations of their grants and accolade amount to travesties of justice. Furthermore, the idea that Creative Australia lack the mandate to discern between promising art and outright hate speech just doesn’t add up. For such a left-wing dominated sector, the sudden penchant for such a laissez-faire libertarian state apparatus in this area alone seems convenient.

In Isiah Berlin’s ‘Two Concepts of Liberty’ (1958), liberty is broken down into two main camps. Some individuals stress the importance of their freedom to act – whether that be a freedom to smoke where they like, to carry a firearm, or to not get vaccinated. This libertarian conception of liberty insists upon one’s right to free speech, best articulated by George Brandis when he said that “people have the right to be bigots”. Liberals insist upon the individual’s right to live life with limited state interference on their freedoms. In Australia, this space is occupied mostly by what we might consider our right wing.

The left wing typically emphasises their right to have freedom from the actions of others, insisting that it is the state’s obligation to protect us from each other. For example, the left might insist upon having the freedom from having to inhale someone else’s second hand smoke, the freedom from having to share space with people carrying firearms lest it increase the chances of someone getting shot, or the freedom from having to risk contracting a contagious disease from someone who has exercised their freedom to not get vaccinated.

Despite the arts being an overwhelmingly left-wing space, its constituents relentlessly signalling their obligation to the policing of language and thought for the common good, an ideological pivot seems to take place the moment that a fear of financial security rears its head. The Memo Review’s Brandis-esque take on the dynamics at play may appear noble, but it is unfortunately as incoherent as it is duplicitous.

Hypocrisy and double standards.

Creative Australia controls the tap that many Australian artists unfortunately must drink from. While I would love to live in a world in which an artist’s labour could be as quantifiable as a copywriter’s, we do not live in this world.

The letter’s viral appeal provides astonishing insights into selective outrage.

Sabsabi himself has no issue with artistic censorship, proudly boycotting the 2022 Sydney Festival for hosting Israeli contemporary dance company Batsheva headed by choreographer Ohad Naharin. Naharin, not unlike many on the Israeli left, is a staunch critic of Israeli government policies in the occupied territories. He has fundraised for the Association for Civil Rights in Israel and participated in public demonstrations for Breaking the Silence — an organisation of veterans dedicated to raising awareness about the human cost of continued occupation.

While all Israelis and Jews like Neharim are fair game for the rabid and shameless Australian art world, Sabsabi enjoys the right to say nothing and be hailed as some testament to artistic freedom.

The inconsistency and selective outrage doesn’t end there.

This isn’t Creative Australia’s first foray into rescinding large grants. Following criticism from Peta Credlin and Bella d’Abrera, the latter referring to the project as “incredibly offensive to Catholics”, Casey Jenkins’ $25,000 Creative Australia grant (then known as the Australia Council) was revoked in 2020. Casey tirelessly reached out for support to limited avail, despite eventually winning their legal action and being awarded damages to the tune of six figures.

Where was Casey’s open letter? Where were Casey’s thousands of signatories? Where was Casey’s support? Or what about Naharin?

How can artists stand here with a straight face and say that Sabsabi has the right to bully someone simply for being a particular nationality?

How can we make sense of the fact that artists have mobilised in their thousands to defend Sabsabi, while either bullying or at best remaining silent while so many of their fellows have suffered from heinous abuse and censorship?

One can’t help but wonder why some causes are so much more safe and so much more fashionable to rally behind than others.

One can’t help but wonder how many hundreds of thousands of taxpayer dollars have been siphoned through Creative Australia to not only placate but reward the radicalisation of some of Australia’s brightest and most promising minds.

The audacity of Memo Review in suggesting that government censorship is posing the biggest threat to the arts is not just laughable, it’s an insult.

Now what?

Perhaps today’s outrage is less about consistency and more about some combination of fashion and fear.

Artists are terrified. Terrified of funding cuts, terrified of each other, and terrified of the ease with which a government body may give and then take away Australia’s most prestigious artistic accolade.

The sad truth is that while the Memo Review were correct to take Creative Australia to task, they’ve turned what should have been an inquest into Creative Australia’s lack of discernment into an ironic tantrum.

The end.

notes to the reader:

1. I feel enough love for the Australian Arts and enough sympathy its cancerous growths that I think it more moral to confine the hundreds of examples of bigotry I have at my fingertips to the bare minimum. The moral dilemma I confront as I write this is: is it better to use no examples to back up my piece, one or two very good examples, or as many as possible?

This dilemma is not a dilemma that is born of a willingness to make my argument as effectively as possible. It is a dilemma that stems from a willingness to balance making my point while causing the least amount of harm to the least number of people.

Going with the ‘no examples option’ would render this piece empty. The ‘few’ examples option runs the risk of appearing to unfairly bully or target certain individuals. The ‘more examples’ approach opens me up to even more retaliation, doxxing, and late-night threatening text messages, as well as of course spreading the harm to more than a carefully selected minority. So options one and three are out.

Option two covers all bases.

If you have any information that might might contribute to this piece or further work, please reach out.

If any of the information above appears misrepresentative or inaccurate please contact me directly at joshua.dabelstein91@gmail.com — I have no interest in misrepresenting any individuals or organisations.

Further reading —

Here is an excerpt of the best thing I have read on this subject so far:

John Macdonald writes:

”Such incidents, and now the Sabsabi wrangle, provide fuel for the pernicious culture wars Peter Dutton sees as a way of gaining favour with a volatile electorate. One can understand Labor’s panic, but these are largely self-inflicted wounds caused by their own board appointments. At CA the lack of fundamental political nous was astonishing, and the resignations and indignation that have followed have only done further damage to Labor’s credentials. What might have been seen as a positive gesture towards Australia’s Muslim communities now looks like a rejection. Jewish communities angered by this episode will not be easily swayed by the about-face.

Perhaps the most noteworthy resignation was that of Lindy Lee, who as a member of the board of CA, put her name to the unanimous decision to rescind Sabsabi’s appointment, only to change her mind the next day, saying: “I could not live with the level of violation I felt against one of my core values, that the artist’s voice must never be silenced”. Such a rapid backflip does not suggest those “core values” were deeply ingrained. It might be unkindly suspected that Lee’s change of heart was prompted by the realisation – after a dark night of the soul – that she could find herself on the wrong side of the ideological fence. Either way, it does not suggest any great strength of character.

Normally, in such cases, I’d incline towards holding firm with the original decision, rather than stirring up a backlash that proves more damaging than the initial controversy. On this occasion, subsequent investigations suggest that perseverance may not have been the best policy.

Now that the door was ajar, a disturbing coda appeared, in the form of a follow-up story in The Australian which investigated the Eleven Collective, a group of Muslim artists initiated by Sabsabi, who appear to have conflicts of interests when it comes to who is applying for and receiving grants, and who is sitting on the selection committees. The story points out that members of the Eleven Collective have received roughly $1 million in grants since 2018.

The peer assessment process has always been a grey area, and it would be difficult to prove collusion rather than business-as-usual. Art appreciation is not a science, and the priorities of a particular group of people chosen to sit on a committee may not square with the views of the general public, or even with an alternative group of art community representatives. That’s the way it is, but it doesn’t make the optics any more appealing. None of this would have come to attention had Sabsabi not been chosen for the Venice pavilion. Now the spotlight will be on these committees, as critics search for more fuel for the bonfire.

As a thought experiment, ask yourself what would have happened if CA had selected a Jewish artist to represent Australia at the next Biennale. Would such a choice have been greeted with acclaim or roundly criticised? Are there Jewish artist collectives that have an equivalent stake in the CA grant processes?

As the week progressed, The Australian’s journos dug a little deeper, and found that CA had also been handing over money to artists who have been singing the praises of assassinated Hamas leader, Yahya Sinwar, on social media. Lest we forget, Sinwar presided over a massacre of liberal-minded Jews who were probably among the most sympathetic group in Israel when it comes to the Palestinian cause. He was one of the masterminds of a strategy that has left Gaza in ruins, and a death toll that is pushing towards 50,000. A real hero, who must have known he was handing Netanyahu and the hardliners who keep him in power, an excuse for a relentless onslaught on Palestinian civilians.

In Australia, our commitment to “freedom of speech” allows people to praise characters such as Sinwar if they so desire. It’s quite another thing for these people to expect handouts from the taxpayer when they have expressed views that are antithetical to the line taken by a government that has been trying to walk a narrow political tightrope between two hostile parties.

The same people who worship Sinwar would be horrified if CA handed money to an outspoken supporter of Netanyahu. As for “freedom of speech, would CA feel OK about supporting to an avowed Neo-Nazi, on the grounds that one’s political opinions are not to be taken into account with any grant application?

The idiocy of those who post hot-headed political statements is that they blindly believe they are right, and therefore should be supported at all times, while their opponents are wrong and must be excluded. It’s no smarter than that.”

Read the rest of this excerpt here.