Please remember to hit like/subscribe, and do consider becoming a paid subscriber if you’d like to support my work.

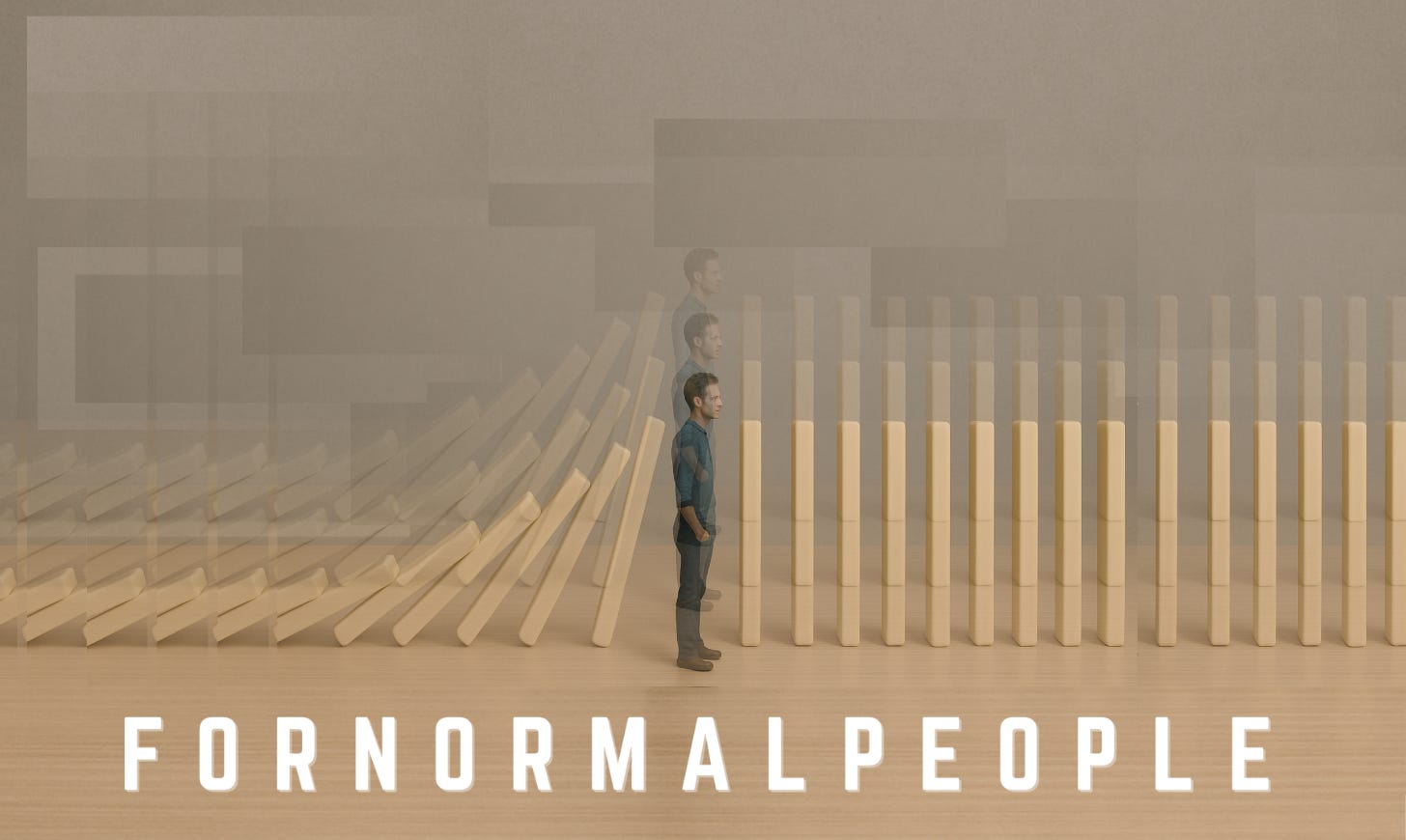

I want you to imagine a line of dominoes as tall as you are.

The dominoes stretch ad infinitum into the horizon directly behind you, and ad infinitum into the horizon in front of you. You stand in this sequence among the dominos, as if having replaced one of them.

The line of dominoes behind you have all fallen, every domino’s fall caused by its antecedent. They rest as all fallen dominoes do, links in a chain of causality receding all the way back to the Big Bang.

In front of you, the dominos remain yet to have been impressed upon by the movement of the past. They represent a sequence of moments yet to have been affected by previous moments. In popular parlance, we call this the future.

The domino directly behind you has been struck and is tilting forwards. In a frozen moment, you turn your head to regard your surroundings.

You look to your left, and then to your right. Eight billion lines of dominoes stand parallel to the line of dominoes that you’re in; four billion or so to your left, and another four billion to your right. Each of these eight billion sequences of dominos house a human at the same precise point as your own, every member of the currently existing human race on the precipice of a new moment shaped by all previous moments.

All eight billion sequences of dominos experience time in lock-step with each other, resulting in the same domino directly behind all eight billion people in all eight billion lines having been affected and caused to tilt by its antecedent simultaneously.

We experience time as one, but not much else.

Why we disagree

Every single human being on the planet experiences reality differently because all of us experience consciousness separately. While the domino behind us strikes all of us at the same time, we experience everything about this new moment uniquely.

In a sense, reality is produced ~8 billion times all at once, with each of these realities being experienced separately. Reality is not therefore a shared experience, but an individual experience. It is generated individually—eight billion times, all at once.

This is why Immanuel Kant’s separation between reality and what we experience reality to be provides a fundamental insight into why human beings disagree on the implications or causes of shared events. What we experience is not the same as what is.

Kant refers to reality as noumena, and reality as we experience it as phenomena.

Consciousness is a translator — translating what is into personal experience.

This distinction exists as a by-product of human consciousness. In processing reality, we re-create it on our own terms. The only element of the noumenal world that we share an experience of is time, illustrated by our identical placement in our own separate domino sequences. All characteristics of a moment beyond how long it lasts are produced internally, subject to our own computations. So while we’re all sharing the same noumenal world, as dominos falling in unison, we’re experiencing separate phenomenal worlds, as dominos appreciating the events inside the passing of time uniquely.

Consciousness is the variable that allows for each human’s unique interpretation of the past, present, and future. Consciousness is an intermediary between moments — it takes a paintbrush to time, creating phenomena from noumena.

Consciousness is an experience created by the human brain, in which data collected from sensory inputs is mashed together with a logbook of previous data and the conclusions one may have drawn from it all, along with projections or inferences one makes about what may happen next. Consciousness constructs an experience of the phenomenal world which presents itself as something each of us identify as reality, despite the fact that the reality we are experiencing is entirely contingent on the uniqueness of each person’s consciousness.

Reality is a projection conjured by one’s consciousness that amalgamates a projection or estimation of all others’ experiences of consciousness — it is a world-building exercise that manifests as the result of our consciousness’s appreciation of the world beyond itself. As I write this, I am existing inside a reality that appears shared, narrated by my own individual conscious experience.

How we disagree

Deviations in reality are produced by the uniqueness of our own phenomenal experiences. Or put simply, reality is not a shared experience.

If we return to regard our place among dominos, we might be able to better understand how the shared experience of a noumenal moment may produce mutually exclusive conceptions of reality.

Let’s consider a real-world example—not to caricature, but to illustrate the powerful divergence of meaning between two people inhabiting the same moment.

After reading three books written by acclaimed authors on Levantine history, Elliot believes that the state of Israel is illegitimate. Over the course of Elliot’s adult life, the social media accounts he follows and the newspaper he subscribes to describe in great detail ongoing human rights abuses against Palestinian people by the state of Israel. On October 7, Elliot’s Jewish friend Sam expresses sorrow, devastated by horrifying footage of Hamas militants executing teenagers, kidnapping babies, and spitting into the caved in heads of young women’s bodies splayed out on Ute trays as they roll back into Gaza.

When Elliot explains to Sam that while he laments the collateral damage caused by an anti-colonial resistance movement, that ‘all resistance is justified on stolen land’, Sam is mortified. Sam attempts to explain Jewish connection to the land. He reminds Elliot that they had all said, as they always do, ‘next year in Jerusalem’, at the end of the seder that Sam’s family had invited Elliot to last year, attempting to re-cap two thousand years of culture and connection to country kept alive in exile despite pogroms, persecution, and Holocaust. He provides ample evidence for Jewish indigeneity, and laments that peacemaking and two-state solutions had been rejected time and time again by Arab leaders on the basis that there should not be any Jewish state at all, regardless of the creation of a Palestinian state.

When Elliot hears Sam explain that his lived experience, culture, education, and preference for compromise and pluralism, Elliot is disgusted. Sam is a Zionist, which means he believes in the ethnic cleansing of Palestinians. Whether Sam realises it or not, Elliot understands that Sam has been raised to weaponise the Holocaust, allowing his people to establish an American proxy state in the Middle East. For Elliot, Sam’s appreciation of history has been warped by the Zionist lobby, who conflate Elliot’s desire to eliminate Israel with a desire to eliminate Jewish people. The Zionists want people like Elliot to accept the existence of a Jewish state, and accuse those who don’t as antisemites.

When Sam tells Elliot that antisemitism is not a form of racism, but a conspiracy theory, Elliot decides that he can no longer have any form of relationship with Sam. Elliot shares screenshots of their conversations online, and Sam moves back in with his parents after having been asked to leave his share house. When someone scratches ‘zioNazi’ into Sam’s car, he reports it to the police. CCTV footage reveals it to have been Elliot’s girlfriend, and Sam receives death threats for ‘collaborating with the police’ for ‘caring more about protecting baby-killers than ending the genocide’.

On November 1st, 2023, Sam watches as a Gazan child’s lifeless body is pulled out from under rubble. Elliot’s social media activity from October 7th, 8th, and 9th is now accompanied by pictures of dead civilians. Sam gets on a plane to Israel, and spends the following 18 months organising protests against the Netanyahu government, and campaigning for an end to the war and the release of the hostages. Elliot sports a Hezbollah flag at a rally on a Sunday in Melbourne, which is confiscated by police, and uploads videos to Instagram about how far-reaching Zionist tentacles are cracking down on free speech.

When Israel bombs Iranian nuclear facilities, Sam spends night after night in a bomb shelter in Tel Aviv. Sam feels strongly that those who repeatedly insist on eliminating Israel and who fund, train, and arm proxies like Hezbollah, Hamas, and the Houthis should not be entitled to nuclear arms, but feels conflicted by the possibility for further civilian bloodshed. From his share house in Northcote, Elliot celebrates on social media as hundreds of ballistic missiles are fired at civilians in Tel Aviv.

Causality: How the unseen past governs the seen world

The only shared experience between Elliot and Sam was a timestamp: October 7. Just two people, next to each other, in their own rows of dominoes.

Both occupied the same moment in time, but the meaning of that moment—the feeling, the interpretation, the moral weight—was refracted through separate chains of causality.

You may turn behind you, count the dominos of moments past, and consider yourself to have an appreciation of history. But how far back can you see with your own eyes, before you’re entirely beholden to someone else’s? And how were those someone else’s eyes beholden, too, to only further layers of dependence on ideologically convenient or psychologically satiating versions of events?

And what of all other ~eight billion sequences? Even your interpretation of history, be it an amalgamation of five other sources or five hundred, is still an interpretation governed exclusively by your own pre-existing motives, values, biases, and shortcomings.

The truth is that when we grow frustrated by others’ realities — be they ill-informed, implausible, or insane — we are misunderstanding reality itself. Remember, while we may share an experience of time, we do not share the experiences produced in time.

We all stand in our own sequence of dominoes. The fallen ones behind us that mark prior events—remembered, inherited, or regurgitated—shape everything about our present moment.

Much of what we call our worldview is assembled, not observed. The lenses through which we interpret events—what feels obvious, what feels outrageous—are constructed from second hand sources: teachers, family, books, rituals, media, institutions, and increasingly, algorithms.

Why should either Elliot or Sam expect their parallel constructions of reality to naturally converge?

The sad truth is that most humans lack the required levels of empathy and self-inquiry to risk falsifying their own narratives. The falsification of our own narratives is made even more difficult when those narratives become symbiotic with our own egos.

Why is this important?

Epistemology—the study of knowledge—is concerned not just with what we believe, but with how those beliefs form and why they endure. We often imagine ourselves to be reasoning, but more often we are remembering, associating, approximating, processes often beholden to broader emotional needs. What we defend in discourse is rarely evidence; it is inheritance. Rarely an idea; more often, an identity.

Disagreement, then, is not usually a collision between opposing truths, but between incompatible sequences of meaning—each assembled from different antecedents, different authorities, different architectures of trust. When those sequences conflict, we do not simply disagree. We fortify.

We are not fighting over the noumenal world, but over the competing narratives produced within the phenomenal one. And when those narratives are challenged, what is activated is not the intellect, but the immune system of the self. It is not a single proposition under siege, but a worldview scaffolded by our own myopia.

The intermediary between the domino behind you and the domino in front is you. You connect the past to the future; your consciousness, in simultaneity with ~eight billion others’, is a meaning-making machine. We are meaning-making machines. Our brains use every passing moment—every space between every domino—to create reality from the mashing together of data immediately available via our senses with some constantly evolving perception of the past. Most of the past, meanwhile, we have no direct experience of.

Epistemological rigidity is as primitive as it is common

The past is re-visitable and re-conceptualizable every time we consider it. It changes in our minds as present events compel us to highlight, emphasise, diminish, or even forget particular parts of it. Histories we are told, well-researched or not, create versions of the past that feel true and real, and these histories hit us in the back and move us forward as a line of dominos strike each other.

The past gathers emotional and epistemic weight as we move forward—its reality reinforced not by new evidence, but by repeated use.

This means that the conditions in which one generates reality change. If how one proceeds is beholden to implacable notions of moments past, then ones freedom to better understand the present is highly limited. If how one proceeds is not beholden to implacable notions of the past, then a far broader array of solutions to any given problem abound. If Elliot had have had the capacity to consider that Sam is morally or logically bound to experience his reality, the pair may have been able to enrich each others’ experiences of the fleeting experience known as life.

It is only in understanding the frailty of our epistemological grounding that we are empowered to better understand ourselves and our contemporaries. The misconception that reality is shared is shattered the moment we understand that while we don’t have to behave like dominos—reacting and acting without agency—we mostly do.

Truth-momentum gathers within societies as they move forward. Scientists falsify their theories in order to edge closer to truth, whittling away at hypotheses. Truth among laypeople is subject to the opposite conditions. Certain narratives become disproportionately encouraged to bloom for the very reason that they are touted by individuals and collectives less-inclined towards the discomfort and destabilising pursuit of self-interrogation.

Or put more simply, history is not written by the victors. We no longer live in a world where 200 men on horseback erase a neighbouring village’s narratives and carve falsehoods into stone tablets to forever be considered history. No. History is now written by consensus.

Consensus is not produced by ‘the victors’, but by those with access to a platform. The democratisation of platforming—whether it be through social media, self-publishing, or as esoteric, useless doctorates produced under flimsy peer-reviewal—allows for the over-writing of nuanced histories with stories that appeal more to our context’s emotional needs than to scrutiny. The irony here, of course, is that those re-writing history truly believe themselves to be occupying the position of the sceptic.

Returning to our dominos

A true sceptic understands that history cannot be re-written or fixed — merely re-interpreted, and that all re-interpretation is a product of a new context. As one of many dominos, in one of many sequences, I am acutely aware of my own propensity to prioritise my own conception of the causal relationship between dominos behind me, beside me, and in front of me. That awareness by no means recuses me from bias, nor from developing moral judgements contingent entirely on the causal frameworks that I inhabit.

And with that said, an appreciation of humanity represented as dominos compels me—and ought compel all of us—to encourage others towards scepticism. We should all endeavour to frame our perspectives as products of unique causal relationships between a past that belongs entirely between our own ears, and a present ruled over by immediate emotional needs.