Shrewd campaign ends on terrifying note

Duping well-meaning Australians into signing onto a 2000-year-old conspiracy.

*Creative Australia have since revoked their revokation. Sabsabi will represent Australia at the Venice Biennale 1.7.25.

When Creative Australia revoked their appointment of Khaled Sabsabi as Australia’s 2026 Venice Biennale representative, an open letter penned by the then-little-known publication Memo Review garnered furious support from thousands of signatories.

The letter felt easy to sign and share, at face value calling for an explanation of any political interference into Creative Australia’s decision-making. As so many Australian artists and creative institutions rely on government grants, artists felt both appalled by Memo’s allegations and grateful for their advocacy.

Within two months of the letter’s arrival Memo Review has morphed from a largely unknown art review publication into something else, publishing clumsily politicised reviews of Sabsabi’s work and hosting a sold-out (yet astonishingly easy to access) panel discussion titled ‘Who’s Afraid of Khaled Sabsabi?’.

Memo’s panel discussion hosted panellists like Louise Adler, who attributed the stifling of artistic freedom in Australia to the ‘zionist lobby’ — a lobby which she likened to ‘big pharma, the mining industry, and the gambling [industry]. Memo were quick to upload clips of Adler’s speech, which have since echoed through the halls of a vengeful arts sector eager to burn the witches responsible for the Sabsabi affair.

How Memo used the momentum from their viral letter, which posed broad questions about transparency in the arts, to disseminating conspiracies about an invisible Jewish hand manipulating the marketplace of free expression in less than two months, requires some contextual appreciation.

For anyone not watching the Australian art world’s conversations and social media accounts over the past eighteen months it may be difficult to understand how drastically a combination of overseas horrors and homegrown disinformation have shaped the sector.

For a sector that prides itself as a hub of independent thinking, its constituents are united on most issues, with debate largely confined to the safety of matters aesthetic and semantic. The streamlining of thought is overseen by systematic “cancellations”, where show trials sully the reputation and earning capacity of the accused non-believer or thought-transgressor.

Some things are allowed, and some things are not allowed.

Many Australian artists, Sabsabi included, boycotted the Sydney Festival in 2022 in order to prevent the work of anti-war, anti-Netanyahu, anti-occupation activist and dance choreographer Ohad Naharin from being performed by the Sydney Dance Company. The Art Not Genocide (ANGA) boycott oversees the prevention of any Israeli artists’ involvement in the Venice Biennale — a boycott also signed by Sabsabi. According to the BDS Movement’s website — the inspiration for ‘cultural boycotting’:

“Israel’s cultural institutions are part and parcel of the ideological and institutional scaffolding of Israel’s regime of settler-colonialism, apartheid and military occupation…”

In Australia’s art sector any involvement with Jews, Australian or Israeli, can only be done on the proviso that this Jew is a ‘good’ Jew, as opposed to a ‘Zionist’ — which has become a slur worse than Nazi or Cop. The only Jews who are allowed to participate have to either openly proselytise that Jews should not have their own state, a crude and malicious party line re-emerging on October 7, or go to great lengths to disguise their souls behind the reasonable doubt afforded to those who keep shtum.

Widespread support for the doxxing of Jewish artists among Australian artists is difficult to criticise without then being accused of ‘supporting genocide’, most conversation in the sector being reduced to a battle of extremes. The sector, instead of engaging with any of these concerns, has proceeded to accelerate the careers of its promulgators.

Director of Canberra Contempory and Deputing Chair of NAVA, Sophia Cai, who has publicly defended the doxxing of Jewish artists as being “in the public interest”, has seen her stature in the arts community grow in congruence with the extremity of her public positions on ‘zionists’.

There has been a longstanding and agreed-upon narrative concerning the Jewish State in Australia’s arts sector, and let me be clear, there is nothing antisemitic about campaigning for the outcomes of Palestinian civilians, or joining me and all those other ‘Zios’ down at the anti-Netanyahu rallies in Caulfield.

What is new — or at least, new in its unchecked prevalence — is the bridging of humanitarian concerns into global Zionist conspiracies by government-funded entities.

Magazines like Debris Magazine, cross-promoted by countless Australian arts institutions like un Projects and West Space — and funded by both Creative Australia and Merri-bek City Council — are now promoting their looming edition complete with writing by some of the sector’s biggest contributors to hate speech, censorship, and doxxing.

Matt Chun, Hoda Afshar, Sarah Saleh, like most writers selected by Debris for their looming edition, have one thing in common, and it’s got nothing to do with contributing to Australia’s arts. They were all excited into antisemitic advocacy before the blood had dried on those teenage girls’ legs splayed out and broken on the dust in the Negev, using their online platforms to either dox and vilify Jewish individuals, or spread conspiracies about a Zionist agenda corrupting Australian free speech.

While these artists are being given government funds and public platforms, Melbourne’s government funded West Space has last week named Tahmina Maskinyar as its new curator. The platforming of figures like Chun, Afshar, Saleh and Cai, and artists like Maskinyar — a former Creative Australia project manager who calls for the eradication of Israel — are only few of the countless examples of a sector plagued with a conspiratorial fixation akin to the Protocols of the Elders of Zion.

If the Zionist lobby were pulling the strings behind the scenes, then why is the Australian arts sector at all levels presided over and funding so many artists who then use the money they’re given to tilt at a ‘Zionist’ windmill?

This is the context in which an emboldened Memo Review has rapidly galvanised the Australian arts public around a conspiratorial paperclip chain linking the de-platforming of Khaled Sabsabi to global Zionist powerbroking. This paperclip chain, strung out over the space of two months, paints an Archibald-worthy portrait of the art sector’s grinding collapse from the creative into the destructive.

In the two months between Memo’s viral letter, and their cards-on-the-table panel event last week, Memo have published reviews of Sabsabi’s Thank You Very Much (2006), and You (2007). These reviews could have been timely offerings to a public hungry for real conversation on Sabsabi’s work, but read as a pair, are not.

Memo’s Rex Butler and Paris Lettau open their remarks on Thank You Very Much (2006) — a short video that stitches together shots of planes flying into the Twin Towers — by likening America’s invasion of Afghanistan to Israel’s invasion of Gaza, asking the reader whether the decision to root out Al-qaeda “sounds familiar?”.

Memo’s writers go on to advocate for the “cancellation” of all Australian Prime Ministers from Howard to Morrison for their roles in international conflict.

Whether one agrees politically with Memo’s writers on this — which to an important extent, I do — the smarmy and cavalier tone in which these remarks are made beggars belief. The advocating of tar-and-feather “cancellation” — a celebration of a disgraceful bullying tactic — should leave any adult signatory to the Memo review troubled.

Memo’s writers then refer to Thank You as, “more like the artist throwing his hands up in the air and saying I don’t know if anybody is right”, before characterising art itself as a “way of starting or joining a conversation without necessarily having something particular to say…”.

It seems unfair that one can hide in ambiguity the moment it is convenient, yet call for the “cancellation” of people or the whose responsibility it is to speak with conviction.

If paperclip one in this chain was the Memo Review’s open letter, paperclips two and three are their reviews of Sabsabi’s contentious works, the review of Thank You ending with a statement that is much better directly quoted than paraphrased:

“Could we pin a moment to the collapse of Western civilisation—the last moment America, as head of the free world, could have done the right thing? It would be when those buildings came down on 9/11, with all those works of art in them. And Bush, after first saying thank you to the firefighters, those who helped search for bodies beneath the rubble, and to all those around the world who sent America their best wishes, then deciding to invade Afghanistan in a second thank you, involving the “West” and “Islam” in a deadly mutual “terrorism” that lasts until this day.”

While this review was quite obviously written and published in response to Creative Australia’s decision, it serves as an ironically validating testimonial for some kind of oversight — what form that should take, I’m not sure. What I am sure of is that Memo’s most recent government grant of $85,300, likely to be matched or increased at Creative Australia’s next opportunity to pander to an angry arts sector, was most likely not overseen by ‘the Zionist lobby’.

Memo’s review of You (2007) is a considerably more mature and considered appraisal of Sabsabi’s work. A very clear argument is made that the work does not “laud” Nasrallah, as was alleged by Tasmanian MP Clair Chandler, but is a complicated portrait designed to convey complex and shifting dynamics.

This third paperclip in the chain from Memo’s letter to Adler’s diatribe returns to the tonal maturity and decorum of Memo’s original letter. While it does still manage to refer in its opening paragraph to Israel’s “disregard and contempt for civilian life”, before then lambasting Australia for providing Israel with “military components”, the review of You reads much less like a manifesto than their review of Thank You.

If Sabsabi’s intention had been for his work to invoke such sentiments on Israel, be they by Senator Chandler or Memo Review’s art critics, then perhaps one could be forgiven for considering his nomination at a time when Synagogues and cars are being torched as ‘high-risk’.

If we weren’t living in a context where anti-Israel speech had so freely flowed into flagrant antisemitism — ironically, well-pushed by an ever-conspiratorial arts-sector — then one would have to wonder whether Sabsabi’s nomination would have ever been considered a threat to ‘social cohesion’ (whatever that means) and by extension eventuated in Creative Australia’s decision to revoke his nomination.

Another important question is whether or not we should have ever expected an entity as risk-averse by design as the Australian government to be able to consistently and thoughtfully fund boundary-pushing creativity. This is the same entity that gave me a $400 fine for falling asleep on a train with my feet on a seat.

Whether in writing letters and reviews, or by hosting panel discussions, Memo not only mirrors the arts sector’s opinions on the Jewish state’s ineligibility to exist, but refashions these opinions into a thesis that pins all grievances with Creative Australia on invisible and nefarious Jewish networks.

Boycotting Israeli artists and cancelling their ability to partake in Australian arts and culture while mobilising around the potential censorship of Sabsabi simply does not amount to the taking of a principled stance against censorship itself. It does however, by following the paperclip chain of Memo’s additions to the dialogue since their viral letter, amount to something far more insidious.

The fourth and final paperclip in the chain of Memo’s logic – a logic designed over a short period of time to incriminate a ‘Zionist lobby’ for perceived Australian artistic censorship — was last week’s aforementioned wheeling out of token Jew Louise Adler.

Videos of Adler’s speech were quickly uploaded to social media by Memo Review, and have spread at a rate befitting a public both angry and eager to identify the witches responsible for the killing of the art world’s sacred cow, Khaled Sabsabi.

From their viral letter, to op-eds posing as reviews, to speeches identifying the Jewish culprits in the woodwork, Memo Review have within a very short space of time constructed the highly readable, shareable, polished and professionally-curated scaffolding necessary for the further dissemination of recycled, divisive, damaging, and contagious conspiracies.

As much as I would like to be able to leave you with a ‘Thank You Very Much’, I have never collected a government-guaranteed paycheque, and gratitude doesn’t keep the lights on. Become a paid or free subscriber below.

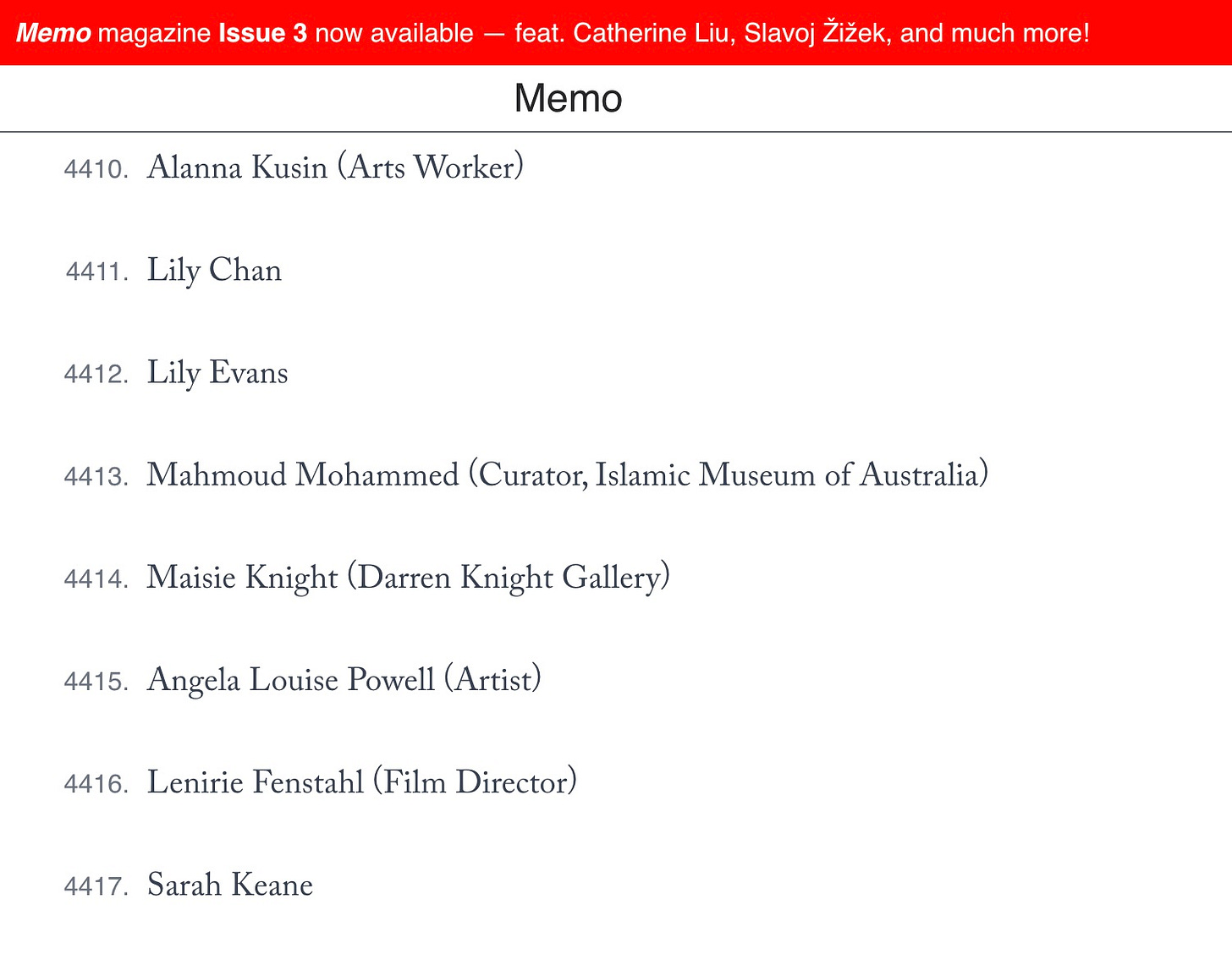

Also, shoutouts to signatory 4416. Very good.